Boredom as a birthright: the luxury of being unreachable

On growing up before screens colonized childhood

I’m eight years old bouncing around all over my purple inflatable furniture while blasting Alanis Morissette’s “Hand In My Pocket,” paying careful attention so I don’t miss my favorite line: And the other one is flickin’ a cigarette. I sing that lyric like someone who lived through the Great Depression. So wise. So already over it all.

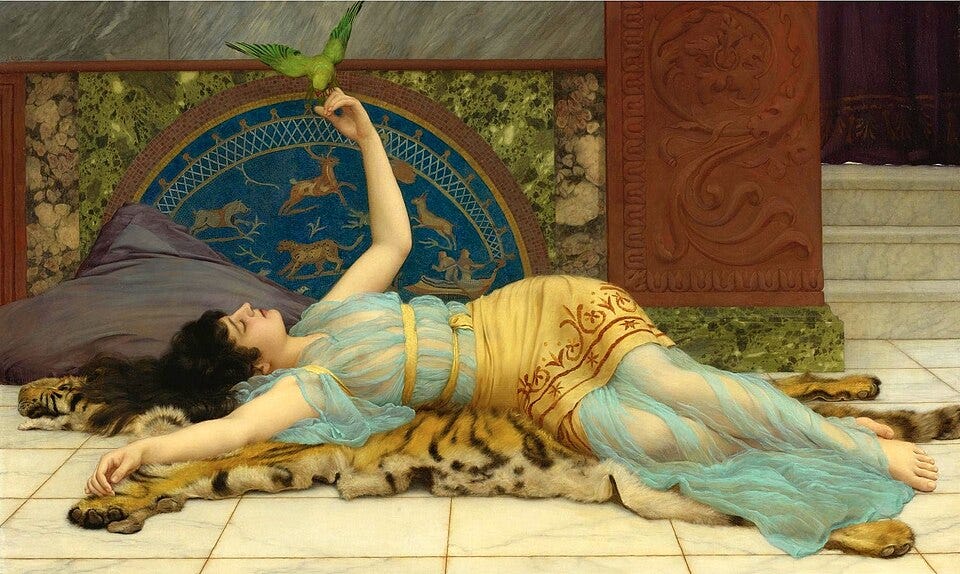

I jump down onto the floor next to my tower of fashion magazines and plop down onto my stomach, legs kicked up into the air behind me. I start flipping through a Vogue, looking for the perfect red missing piece for my vision board.

I pause to sing at the top of my lungs:

And what it all comes down to, my friends, yeah

Is that everything is just fine, fine, fine!

When I closed the door to my bedroom, it was like nothing else in the world existed. I was immersed in my own little world and could keep myself occupied for hours on end. My mom would have to come get me just to remind me to eat. Between my journals, mood boards, music, karaoke machine, encyclopedias, and sticker books, I couldn’t bother to be bothered.

We didn’t have a giant house or a ton of money, but I had a door that closed and a lot of time to kill, and that was more than enough.

At my grandparents’ house, the immersion looked different—less interior design, more feral creature. I was outside from the moment I woke up until someone made me come in. Riding bikes in circles around the neighborhood, crouching in the dirt examining bugs like a scientist with zero credentials, hiding in bushes trying to catch birds, playing with my grandma’s dog. My grandma also had a tortoise named Speedy that I’d build little racetracks for. He lived up to his name exactly never.

My grandparents had a motorhome parked in the backyard, and sometimes I’d get to “camp” in it. I’d set the whole thing up like my bedroom back home—my own little mobile headquarters—and my grandma would bring me dinner like I was some kind of dignitary stationed in the wilderness. I loved that. Being alone but not lonely. Having a world that was entirely mine, even if it was just a converted RV in a suburban backyard.

If it rained or my grandma forced me inside, I’d sit with her and watch cartoons. But mostly I wanted to be out there, in my head, in the dirt, watching things… wondering about things.

I hardly ever watched TV as a kid. We had Disney VHS tapes and I’d pop one in occasionally, but screens weren’t the default. They weren’t the thing I reached for when I was bored. Boredom was something else entirely back then… it wasn’t a problem to solve, but a doorway. A slow, uncomfortable pressure that eventually cracked open into something. An idea, a project, a three-hour investigation into whether I could teach myself to whistle with my fingers. (I couldn’t.) (I still can’t!)

I think about this a lot now. About what it meant to grow up with that kind of unstructured time and uninterrupted interiority.

I keep coming back to this phrase: the luxury of being unreachable. Because that’s what it was, even though I didn’t know it then. No one could find me when I was in my room with the door closed. No notifications, no pings, no algorithm feeding me the next thing before I’d even finished the first thing. My attention was mine. I could give it to a magazine page or a beetle or a song lyric I was trying to decode, and nothing was competing for it.

Kids now don’t have that because the environment is so different. The phone is always there, the iPad is always there, the dopamine hits are always there—and they’re engineered by people who understand human psychology better than most humans understand themselves. It’s not a fair fight.