Common sense is dead

Thomas Paine and the lost art of reasoning—250 years later

Everyone thinks they have common sense, but few people actually use it.

The phrase has become a way to end thinking rather than begin it. “It’s just common sense” means “I shouldn’t have to explain myself.” It’s a claim to reasonableness that skips the actual reasoning. We invoke common sense to avoid the work of thinking, not to do it.

Which makes it worth remembering what the phrase originally meant, and the man who made it famous.

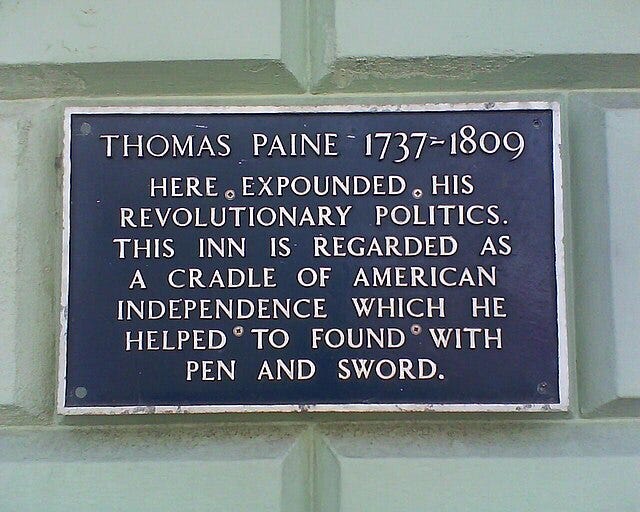

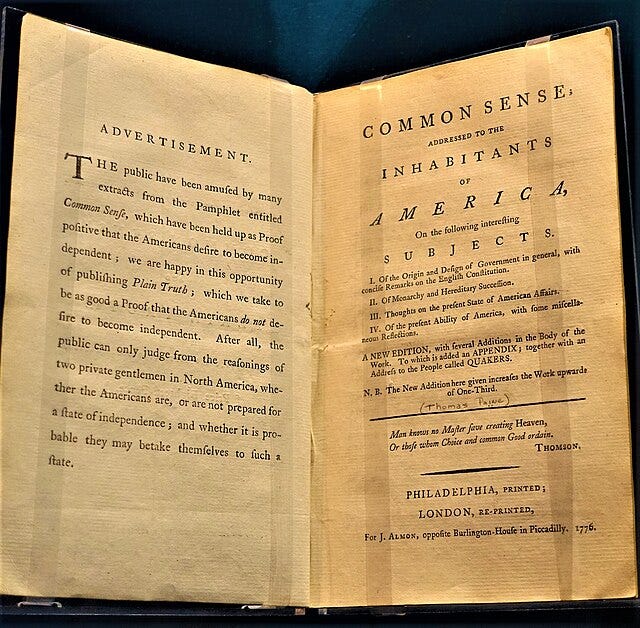

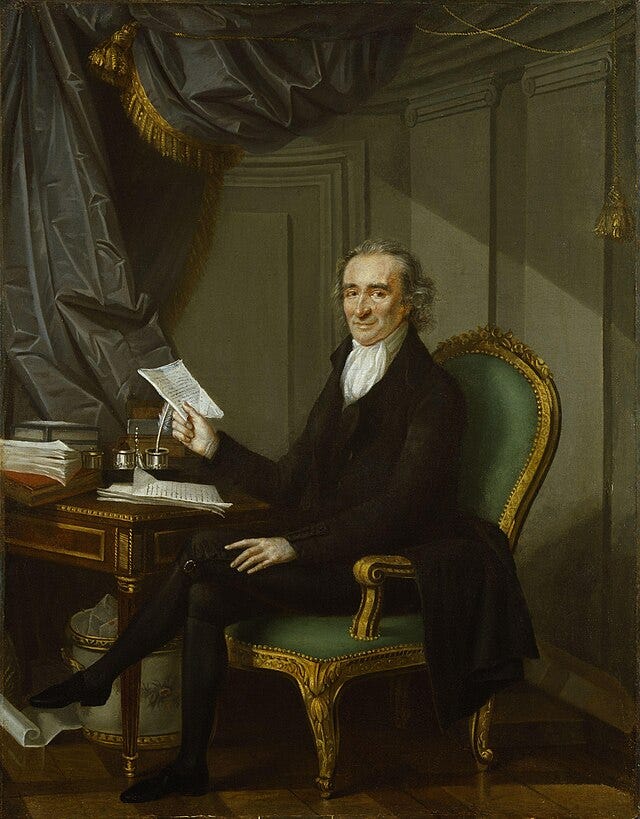

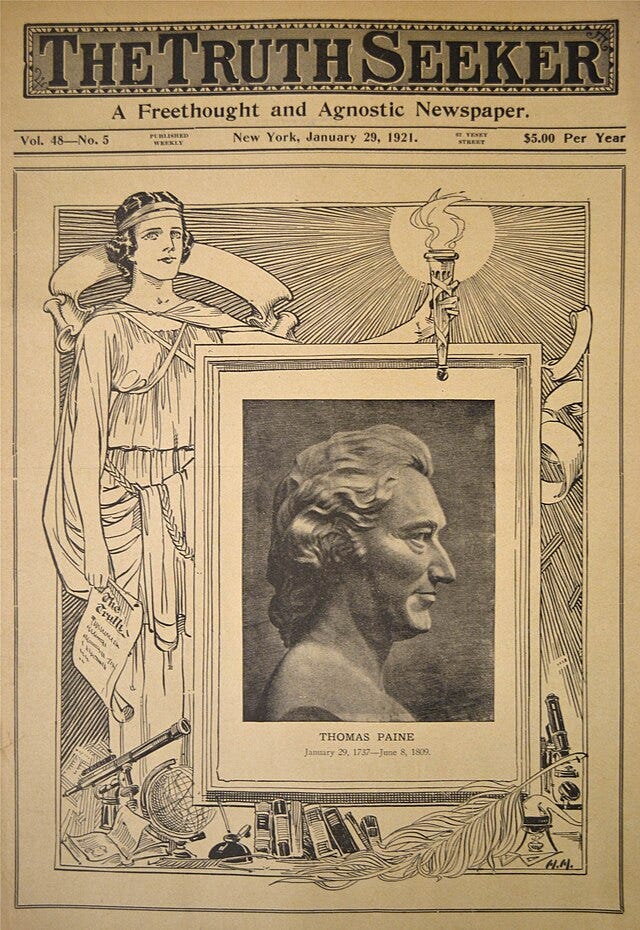

250 years ago today, Thomas Paine published a 47-page pamphlet in Philadelphia. He was a broke, twice-divorced English immigrant who’d been in America for barely a year. Within twelve months, an estimated 20 percent of colonists owned a copy. People who’d spent a decade debating how to negotiate with Britain were suddenly asking a different question entirely: why do we have a king at all?

Paine called his pamphlet Common Sense because he believed ordinary people could reason their way to political truth, without priests, kings, or credentialed elites interpreting reality for them. He wasn’t making an argument for a specific policy, he was making an argument that his readers were qualified to think for themselves, and that they’d been waiting for permission they didn’t need.

What made Common Sense explosive wasn’t just the argument. It was the method.

Paine didn’t argue within the existing frame—how should colonies negotiate with the Crown, what rights do British subjects have, which taxes are legitimate. He went underneath the debate entirely, asking why would anyone accept hereditary rule in the first place? What’s the argument for monarchy that doesn’t rely on “this is how it’s always been”?

That’s first principles thinking. You don’t start from the inherited assumptions, rather you ask what you can verify yourself, from the ground up. Paine looked at monarchy and asked: if we were building a government from scratch, would anyone propose this? A system where power passes to whoever happens to be born next, regardless of competence or character?

The answer was obviously no, but people couldn’t see it because they were reasoning within the system rather than about it.

Paine also understood that monarchy wasn’t just a bad idea floating in isolation. It was an interlocking structure—crown, church, aristocracy, tradition—where each piece reinforced the others. The king was legitimate because the church said so, and the church was authoritative because the king protected it, which meant the aristocracy was natural because it had always existed. To question any piece, you had to see the whole system and how it kept itself in place.

That’s what made the pamphlet dangerous. He wasn’t just arguing against a policy, he was exposing the entire operating system.

He also wrote short sentences in plain language. He didn’t quote Greek philosophers or appeal to legal precedent. He assumed his readers could follow a logical argument without credentials, and that assumption itself was radical at the time. The pamphlet was cheap, accessible, and everywhere. Read aloud in taverns, passed hand to hand, reprinted across the colonies.

Plus, Paine was fast. The system he was attacking was slow, layered with tradition and deference. Paine moved faster than institutions could respond, so by the time loyalists published rebuttals, the frame had already shifted.

That was 1776. The problem now is the opposite.

Paine was faster than the system. Now the system is faster than you.

Opinions arrive faster than thought. The feed generates an endless stream of positions you can adopt without ever reasoning your way to them. People don’t need to be convinced, they need to be sorted. Are you on this side or that one? This tribe or that tribe? Here’s your script.

“Common sense” has been hollowed out. Paine meant it as a method—reasoning from first principles, without deference to inherited authority. Now people treat it as some kind of credential. A way to signal you’re reasonable without doing any actual reasoning. When someone says “it’s just common sense,” they’re claiming a conclusion, not showing their work.

And it goes deeper than sloppy language. We’ve built an entire culture around outsourcing judgment. The message, everywhere, is the same: don’t trust yourself, trust the system. Trust the feed. Trust the people who know better.

Paine’s readers had been trained to defer to kings and priests. We’ve been trained to defer to feeds and credentials.

So what would it look like to reclaim common sense—not the phrase, but the practice?

Start by seeing the system.

Paine understood that deference to monarchy wasn’t a personal failing, rather it was produced by an interlocking structure that made certain questions feel unaskable. The system perpetuated itself—not through force alone, but by shaping what people could even imagine.

We have our own version. Algorithms curate what you see. Credentials determine who you trust. Partisan media feeds you pre-sorted conclusions. Social incentives punish deviation. Each piece reinforces the others. The feed rewards speed, not reflection. Credentials create deference to expertise even when experts are wrong. Tribal sorting makes independent thought feel like betrayal.

Much like Paine's readers 250 years ago, you can't think clearly about a system while you're still deferring to it.

First principles is the way out. Instead of asking “which side of this debate am I on,” you ask: what’s actually true here? What can I verify myself? What would I believe if there were no social consequences—if no one was watching, if my tribe would never know?

That’s harder than it sounds because your gut has been trained. Your instincts have been shaped by the same system you’re trying to see past. Common sense, reclaimed, isn’t about trusting your reflexes, it’s about questioning where your reflexes came from.

It also means tolerating disagreement differently. Paine wasn’t asking readers to agree with him, he was simply asking them to think without referees. What made Common Sense work wasn’t unanimity, it’s that people encountered an argument that didn’t signal allegiance to any existing authority. No king. No party. No tribe. Just reasoning laid bare.

That condition barely exists now. Most disagreement isn’t independent, it’s choreographed. Scripted outrage, borrowed language, predictable objections delivered on cue. That’s not thinking. In fact, that reeks of compliance.

Paine gave people permission to think faster than their institutions. The task now is permission to think slower than the feed.

In practice, this means developing habits that run against the current.

Notice when you’re borrowing a conclusion.

There’s a difference between thinking something and having heard something so many times it feels like your own thought. If you can predict exactly what your side would say about an issue, and you’re saying it, ask whether you reasoned your way there or absorbed it.

Find the question underneath the debate.

Most arguments are fights over which answer is right. First principles asks whether the question is even framed correctly. Paine didn’t engage the debate about colonial rights within the British system—he asked why the system existed at all.

Ask what you'd believe if no one were watching.

Pick an issue where you know your tribe's position. Immigration, climate, guns, whatever. Now imagine you couldn't be punished or rewarded for your view—no social consequences at all. Does your position shift? Does it get more nuanced? Do you suddenly feel less certain? That gap between your public position and your private uncertainty is where the work is.

Distinguish between “I disagree” and “my tribe disagrees.”

Independent disagreement sounds like: “Here’s where I think your reasoning breaks.” Tribal disagreement sounds like scripted outrage. One advances understanding. The other is performance.

Hold conclusions loosely.

First principles thinking isn’t about reaching the “right” answer once and defending it forever. It’s a practice. You keep asking. You revise. You notice when the evidence shifts. Certainty is often a sign you’ve stopped thinking.

The point isn’t to reject all authorities or trust no one, it’s to know the difference between reasoning and deference—and to catch yourself when you’ve slipped from one to the other.

250 years is a long time. Why does any of this matter now?

Because the conditions that made Common Sense resonate so deeply are back.

Paine wrote for a population experiencing quiet cognitive dissonance. People could sense that the system wasn’t working—that the official story didn’t match reality—but they didn’t have language for it yet. They were waiting for someone to say what they already half-knew.

That’s where we are. Institutions are visibly decaying, expertise keeps getting it wrong, public discourse is theater. Everyone can feel the gap between what’s claimed and what’s true, but most people stay quiet, waiting for permission, unsure if they’re allowed to even notice.

Paine’s insight was that the permission isn’t coming. Not from credentials or institutions or from your tribe. The only way out is to think for yourself—carefully, slowly, from the ground up—and to trust that other people can do the same.

That’s what common sense actually meant. Not a conclusion everyone shares, but a capacity everyone has.

The question is whether you’ll use it… or keep waiting for someone to tell you what you think.

—S

This post was really good! I mean it's a really good insight on what common sense was actually about.

This post is brilliant. Made me immediately think of 4-5 years ago and “Trust the experts (but only these few we picked for you)”.

It is invigorating to find more people and content being open to simply hear, express or consider thoughts beyond “my tribe”.