The art of being your own muse

When we talk about the idea of “being your own muse,” it’s easy to drift into a vague, romanticized notion of self-admiration. We tend to picture a woman lounging on a chaise, waiting to be admired into meaning, some beautiful, ethereal creature whose only job is to exist prettily enough that a genius notices her and makes something of value. But if you strip away centuries of misinterpretation and look at the actual mythology, specifically the image of Apollo surrounded by the Nine Muses on Mount Parnassus, you realize that the dynamic is completely different. The Muses were never passive ornaments waiting to be chosen. They were engines of knowledge who governed astronomy, mathematics, epic poetry, sacred hymns, and memory itself. Each one presided over a specific domain of human understanding, and they didn’t receive inspiration so much as they generated it. Apollo wasn’t selecting them from some cosmic lineup; he was drawing from them, immersed in their intellectual force.

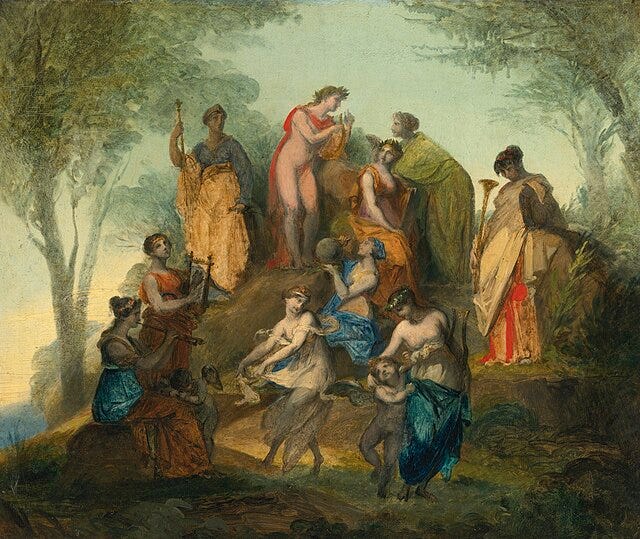

In the classical imagination, Mount Parnassus was the blueprint of where ideas actually came from. While Apollo represented the organizing principle of light and prophecy, the Muses provided the substance. They were his extensions and the embodiments of specific intellectual energies. If you look closely at Pierre-Paul Prud’hon’s depiction of this scene, or really any classical representation, you will notice something crucial. None of the Muses are gazing dreamily into space waiting to be adored. They are actively working, they’re playing instruments, teaching, engaging with each other, and thinking. The muse wasn’t the one being looked at, because she was the force doing the illuminating.

Somewhere between ancient Greece and the modern era, we inverted the whole concept. We stripped the Muses of their sovereignty and turned them into decorative objects. The muse became the “manic pixie dream girl” or the beautiful distraction, the woman who exists solely to unlock a man’s genius without having any of her own. We handed all the creative authority to whoever was doing the looking and turned the muse herself into raw material to be consumed. But the actual function of a muse is much simpler and much more democratic.

A muse is just a source of orientation, something that directs your attention and pulls your focus toward what matters. And I can’t think of a single reason why that source of orientation can’t be you.

I think we resist this idea because we’ve been trained not to trust our own inner lives. We confuse external validation with internal ignition, believing that breakthroughs come from reading the right book, finding the right mentor, or hearing the right piece of feedback. We wait for someone else to tell us we’re onto something before we believe it ourselves, but creativity doesn’t actually work like that. It is endogenous. It emerges from inside, from the specific architecture of your own mind making connections that only it can make.

This is where the neuroscience actually supports the mythology. Your brain’s “default mode network” is the system that activates when youdaydreaming or letting your mind wander without trying to force it anywhere. This network is exactly where disparate ideas connect and where patterns emerge that you couldn’t have planned. Insight doesn’t fly in through the window, it bubbles up from deep in your own consciousness. The ancients understood this better than we do. They personified these interior forces as goddesses because they recognized that creativity feels like it comes from somewhere beyond your conscious control, but they located those goddesses on a mountain you could climb. They made inspiration accessible rather than some distant benediction you had to wait for.

We have lost that accessibility largely because we’ve been conditioned to distrust our own impulses. This gets harder every year we spend living online, where the algorithm rewards mimicry over originality. Scroll through any platform long enough and you will see the same ideas, the same aesthetic choices, and the same cadences repeated until they lose all meaning. Most people don’t even know what they actually like anymore, they only know what performs, what gets engagement, and what signals membership in whichever tribe they have allied themselves with. When you outsource your identity to trends and carefully curated aesthetics, you lose the ability to hear your own signal underneath the noise. You end up waiting for external cues about what to think and make, effectively becoming the modern version of the passive muse—arranging yourself decoratively in hopes that someone will notice and give you permission to matter.

The art of being your own muse means returning to that original definition where inspiration comes from intellect, curiosity, and aliveness. It means recognizing that you contain the same multiplicity the Muses represented. You have your own internal astronomy and mathematics and poetry. You have memory, which is where all creativity actually starts. You don’t need to import these capacities from somewhere else, you need to cultivate them, pay attention to them, and take them seriously enough to let them guide you.

This isn’t about walking around feeling perpetually inspired and magical. That’s still a fantasy, and honestly it sounds exhausting. Being your own muse means referencing yourself first, studying your own mind with the same attention an artist brings to a landscape, paying attention to your energy, noticing what depletes you and what generates heat, and designing your environment around your own signals rather than someone else’s template. It means treating your own curiosity as the highest authority in the room.

The women I find myself returning to, the ones whose work still feels alive decades or centuries later, understood this instinctively. Frida Kahlo painted herself obsessively, not out of vanity but because she refused to wait for someone else to interpret her reality. She was both subject and artist, collapsing that false distinction between muse and maker. Georgia O’Keeffe walked away from the entire New York art establishment to cultivate her vision alone in the New Mexico desert, literally removing herself from the scene where she might have been reduced to ornament. Anaïs Nin used her diaries as laboratories for understanding her own consciousness, treating her inner life as the primary text worth studying. They didn’t wait to be chosen or discovered or validated. They generated their own gravity, and the world reorganized itself around them as a consequence.