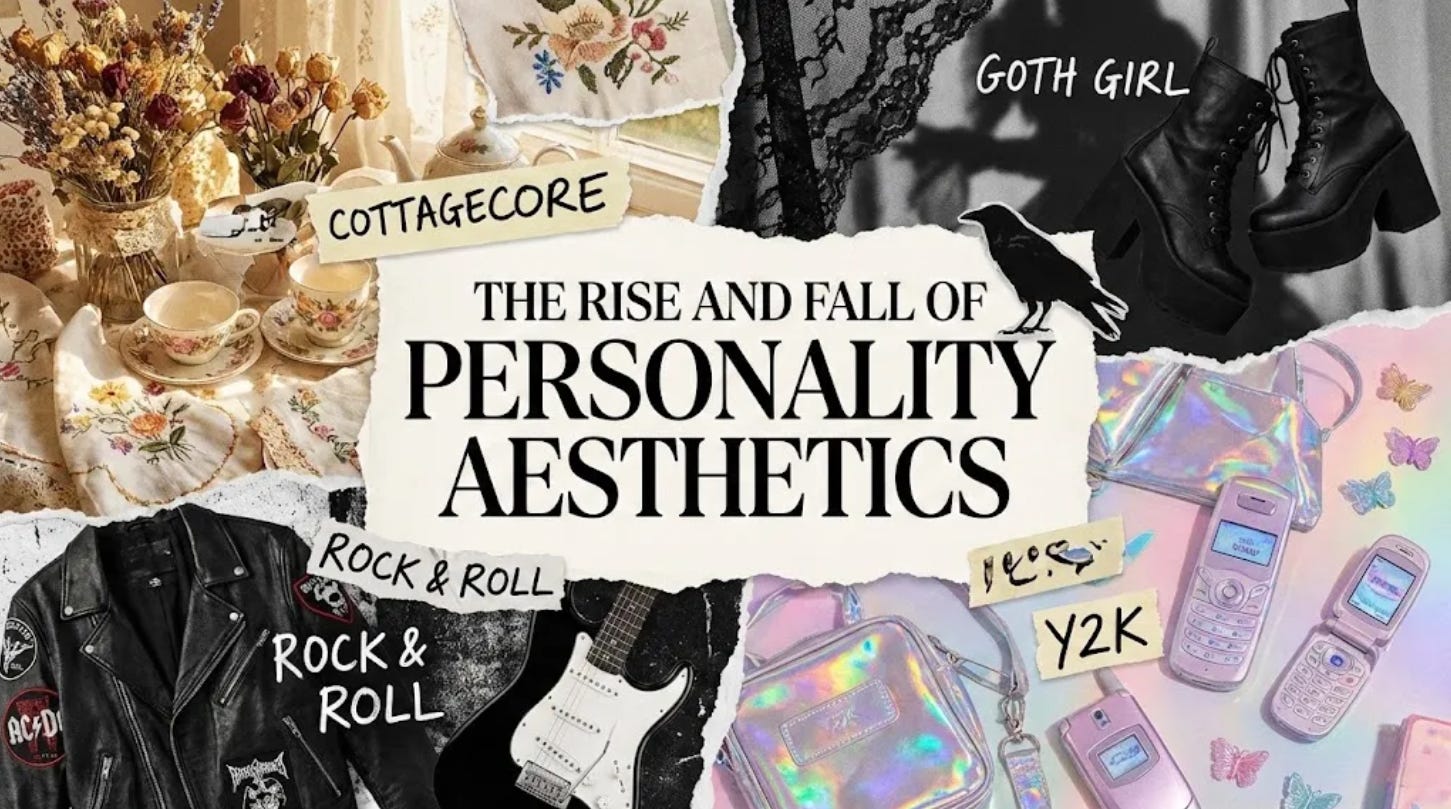

The rise and fall of your personality aesthetic™

The difference between becoming someone and pretending to be someone

Hello and happy weekend. Below is one of my weekly posts exclusively for paid subscribers to BAD GIRL MEDIA. As a paid reader, you help make this newsletter a consistent, sustainable part of my life. Also, you get 3x the number of essays from yours truly! Thank you so much for reading bad. x

If you’re new here, you can explore my full archive chronologically, or browse by theme using the glossary of thoughts.

This week’s free essay: The audience of none (part 2): what happens when you actually stop performing

I have a tattoo sleeve on my left arm that I started getting when I was eighteen. Sometimes I catch sight of it in the mirror and think, “Why the fuck would I do this to my body?” The answer, which took me years to admit, is pretty painfully straightforward: Besides having a prefrontal cortex that hadn’t fully developed yet, I had unresolved trauma. I needed to do something visible and permanent to my body because I couldn’t articulate what was happening inside of it. The aesthetic choice came first. The self-knowledge came later, after it was too late to take it back.

To be clear, I’m not hating on everyone with tattoos, nor am I claiming everyone who modifies their appearance is working through something broken. But I do think there’s often a correlation between radical aesthetic shifts and internal chaos we don’t know how to process. We change the outside when we can’t change the inside, by trying on new versions of ourselves and hoping one of them will finally feel right. And sometimes that experimentation is healthy, necessary even. Sometimes it’s how you figure out who you are. But sometimes it’s just elaborate avoidance that we like to pretend is self-discovery.

I deleted my Instagram almost 5 years ago, which means I’ve been spared the algorithmic ritual of watching my own archive resurface like evidence at a trial. But I still have my camera roll, and sometimes late at night I scroll back through it like an anthropologist studying a civilization I used to inhabit. There’s me in 2021, apparently convinced that wearing linen and reading Rilke made me a person of substance. There’s me in 2022, having pivoted to what I can only describe as “feral desert witch attempting a bohemian lifestyle.” There’s me six months ago in an outfit I genuinely believed represented my authentic self, which I now wouldn’t wear to take out the trash.

It’s almost as if every few years, you wake up and realize you have no idea who you’ve been performing as. Your old tweets read like they were drafted by a stranger with unresolved issues. Your Spotify Wrapped reveals you spent an entire season pretending to be someone capable of sustained joy. The evidence accumulates in layers, like geological sediment, each stratum documenting a different version of you that felt absolutely certain it had finally figured things out.

All to say, personalities aren’t stable. I know we like to pretend they are, like there’s some essential core self we’re all working to uncover, but I’m increasingly convinced that’s a comforting fiction. What we actually have are aesthetic eras. Modular, seasonal, occasionally delusional attempts to impose coherence on the chaos of being a person. We cycle through them like fashion trends, except the stakes feel higher because we’ve convinced ourselves that this time, this version, is the real one.

You know the exact pipeline I’m talking about. Clean girl to feral girl summer to quiet luxury to trad wife to whatever renaissance painting cosplay is currently trending. Our personality aesthetic used to be shaped by slower forces. Books you actually finished, friends who knew you well enough to call you on your bullshit, teachers who challenged how you thought, travel that genuinely disoriented you. Now it’s shaped by whatever trend TikTok is pushing this week to fill the void where a self used to be. We’ve stopped building identities and started downloading them like some kind of plug-and-play persona, optimized for maximum aesthetic coherence with minimum internal examination.

I’m not exempt from this. In fact, I opened with my tattoo tragedy as a kind of peace offering and show of good faith for all I’m about to write next. I’ve moved through enough aesthetic eras that I could teach a masterclass in self-reinvention. When I first moved to Vegas, I went full rock and roll girl. Doc Martens every single day. Everything I owned was black. Black eyeliner, black hair, black jeans, black t-shirts. I looked like I was auditioning for a band I didn’t even want to be in. Then there was a transitional phase where I had emerald green hair, which in retrospect feels like my psyche trying to signal that the all-black era was dying but I hadn’t figured out what came next. I was experimenting, trying things on, seeing what fit.

But the part I couldn’t see while I was doing it was, I wasn’t just experimenting with aesthetics, I was using aesthetics to avoid looking at what was actually happening underneath. The rock and roll girl wasn’t exploring her identity, she was hiding from it. The aesthetic gave me something coherent to perform while my actual life was falling apart in ways I didn’t want to examine. It was easier to focus on what I looked like than to deal with why I felt the way I did.

The thing that’s changed isn’t that I’ve stopped cycling through identities, it’s that I’ve started paying attention to the machinery underneath, trying to understand what these shifts actually mean and why they feel so urgent in the moment and so embarrassing in retrospect.

Christopher Lasch wrote about this decades ago in “The Culture of Narcissism,” though he couldn’t have predicted how thoroughly the internet would accelerate the process. He was talking about a culture that had lost the ability to form stable identities, that treated the self as an ongoing performance requiring constant management and revision. Zygmunt Bauman called it liquid identity, this sense that nothing about who we are gets to be fixed or solid anymore. Adam Curtis made an entire career documenting how we’ve aestheticized ourselves into oblivion, turning inward not for genuine self-knowledge but for more refined ways to package ourselves for public consumption.

The strange thing is that these identity shifts feel euphoric when they’re happening because a new personality aesthetic doesn’t feel like a costume, it feels like salvation. It promises reinvention. It gives you narrative control over a life that otherwise might just be a series of random events happening to a confused animal. It supplies the illusion of momentum, which is sometimes more valuable than actual progress because at least you feel like you’re going somewhere.

There’s actually psychological research on this—the fresh start effect. People change more readily after symbolic reset points like New Year’s Eve, birthdays, breakups, or moving to a new city. A personality aesthetic is basically a self-administered reset button, a way of telling yourself that this time it’s going to be different, this time you’ve figured out the right way to be.

And sometimes that’s exactly what you need. Sometimes you do need to reinvent yourself to move forward. The problem is learning to distinguish between reinvention as growth and reinvention as avoidance.

Every aesthetic era eventually hits a wall. It stops feeling aspirational and starts feeling like a costume you can’t take off. The wellness girl who built her entire identity around adaptogens gets bored and realizes she’s been performing health rather than experiencing it. The peak minimalist discovers that beige is a prison and that owning seventeen items doesn’t actually make you more enlightened. The crypto guy whose entire personality evaporated when the market dipped, leaving him with nothing to talk about at parties except a vague sense that he used to be someone he thought was cool.

The persona collapses for predictable reasons. It becomes too performative and it stops reflecting your internal state. The trend cycle accelerates past you and suddenly you’re embarrassingly dated. You grow, but the aesthetic you’ve committed to doesn’t grow with you. Maintaining it becomes labor instead of expression, and before you know it, you start to feel like you’re managing a brand rather than living a life.

Baudelaire wrote about this in the nineteenth century, this double consciousness of the modern self. The tension between your inner life and the performed version you present to the world. He was talking about flaneurs wandering Paris, but it’s the same fundamental problem. Your aesthetic era stops fitting your actual psyche and the gap between who you are and who you’re pretending to be gets wide enough that you can’t ignore it anymore.

I think these personality aesthetics are actually psychological defense mechanisms, which sounds dramatic but tracks with how urgently we cling to them. They’re not superficial, they’re adaptive. They protect us from uncertainty, from emotional exposure, from chaotic internal states we don’t know how to process. They give us something to be when we don’t know who we are yet.

Jung wrote about the persona as the mask you wear when you’re still figuring yourself out. It’s not fake, exactly. It’s functional. It’s the scaffolding you need until you can stand on your own. Your brain prefers patterns, craves them actually, and a personality aesthetic provides a stabilizing pattern during periods of flux. The woman who starts wearing all black after a chaotic breakup isn’t being shallow, she’s using aesthetic constraint as mood regulation, creating external order when her internal world feels like it’s disintegrating.

I did exactly this after I quit drinking and deleted social media in 2020. I completely rebuilt my entire aesthetic, my routines, even my social patterns. I needed a new way to be because the old way had stopped working. The aesthetic era wasn’t the solution, but it bought me time. It gave me something coherent to perform while I figured out what was actually happening underneath.

The question is whether you’re using the aesthetic as a bridge to somewhere real or as a permanent substitute for doing the actual work of figuring yourself out. And the honest answer is that most of the time, you don’t know which one it is until later. You can’t always tell in the moment whether you’re experimenting your way toward clarity or just cycling through identities to avoid sitting still long enough to face what’s actually wrong.